Issue #1 - Rudland - Co-creating with Improvisation for Community Opera

Co-creating a Brass Band Dance Number for a Large-scale Community Opera Project with the Aid of Improvisatory Techniques

Oliver Rudland

Abstract

Community opera projects have often integrated bands of varying types to involve participants in ways other than singing and acting. Although many community opera projects incorporate co-creative elements and improvisation techniques in their composition there is little coverage of how bands, in practice, can be involved as participants in the co-creative process of shaping a new community opera.

This paper documents a practice research project that took place with Waterbeach Brass Band based in Cambridgeshire, UK. It records in detail the process whereby aspects of a brass band dance number were devised during co-creative improvisation workshops and provides both audio-visual recordings and notated examples that capture the emergent creative process, alongside a commentary explaining the processes and approaches employed. The paper examines the different ways in which members of the brass band responded to improvisational workshops, and how this fed into the co-creative process. The paper then proceeds to examine how such co-creative elements can then form part of a larger musical-dramatic presentation, demonstrating how they can be developed during an extended operatic scene, as well as considering the risks, responses and rewards of the process.

Introduction

Group improvisation has been a common technique deployed in the activity referred to as ‘community music’ from at least the 1960s. In pragmatic terms, ‘community music’ generally involves a collaborative interaction between professional musicians and community participants in the performance and creation of new music (Higgins, 2012). Beginning around the 1980s, the practice and methods of community music began to influence the work of opera houses and composers writing ‘community operas’ in the UK (Shahryar, 2019). Prominent amongst these composers was Jonathan Dove, who composed three community operas involving improvisatory techniques commissioned by Glyndebourne Opera House (Dove, 1999). For example, In Search of Angels (1995) set during the English Civil War. Working on these operas, Dove recollects that:

I developed a more playful way of working, finding different ways of getting groups improvising together in song (while stamping and clapping and even dancing), splitting into groups to try out several different ways of singing just one or two lines of a libretto, then all gathering around the piano to stitch the fragments together: this process often led to surprisingly organic melodies. Obviously, from the piano, I had a hand in shaping the music, but there was always a sense of collective achievement, and shared ownership.[1]

Many other composers involved with community opera projects have been inspired by this approach, for example John Barber (Barber, 2015). This was due in part to the establishment of ‘education’ departments in UK Opera Houses from the 1980s onwards and the opportunities these departments offered to composers to work in community settings (Winterson, 2010). However, there are no published accounts of how improvisational techniques can be used to develop musical material involving participants in ways other than singing and acting; particularly the use of onstage musicians such as bands. Onstage bands are often integrated into community opera projects. In Search of Angels, for instance, incorporated the entrance a samba band procession to represent Oliver Cromwell’s Army (Deane, 1995).[2]

Commentary

The following documents a practice research project that took place with Waterbeach Brass Band, a community band based in Cambridgeshire, UK. During this project a swing dance number for a community opera was co-created with the band.[3] The community opera is based on Barry Hines’ novella A Kestrel for a Knave (1968) which is set in a Yorkshire coal mining town during the 1950s; it was in the context of such industrial communities that the British brass band evolved (Herbert, 2010).

One scene takes place in a pub where a brass band are playing some swing music to accompany a dance; contemporary dance music during the 1950s was often replicated like this in such social settings.[4] To provide the basis for an improvisational workshop, therefore, some backing music was composed in a 1950s swing style akin to the big band arrangements of Benny Goodman or Glenn Miller, except scored for brass band.[5] During a preliminary rehearsal, the backing music was rehearsed by Waterbeach Brass Band and the following example is an excerpt presented in short score for convenience, along with an audio recording:

Example 1:

Recording 1: https://soundcloud.com/oliverrudlandresearch/brassbandexcerpt-1

Waterbeach Brass Band consists of non-professional musicians aged from 18–70. Although they are not a group generally accustomed to improvisation, most do have good musical training in reading notation and basic music theory. Therefore, to begin the co-creative workshop, some initial exercises were undertaken using techniques familiar to community musicians, rather than leaping straight into improvisation with the backing music.

First, in order to loosen up the band and get them used to playing away from notated music, the individual players were invited to contribute notes to a tutti cluster chord, making their way up from the lowest instruments to the highest:

Recording 2: https://soundcloud.com/oliverrudlandresearch/brassbandexcerpt-2

This was practiced several times to explore different combinations and harmonies. Next the band were asked to elaborate around their chosen notes and to improvise freely as a group:

Recording 3: https://soundcloud.com/oliverrudlandresearch/brassbandexcerpt-3

Following these free exercises, the band were given some scale sheets to assist improvisation with the backing music:

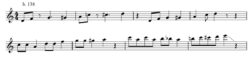

Example 2: Solo Cornet in B-flat

The four scales provided included the ‘blues scale’, which would sit comfortably on top of all the backing music. Additionally, a ‘natural minor’ scale and a ‘tonal minor scale’ (both from the melodic minor scale in C minor, the key of the backing music) were added, so as to increase the sophistication of the materials for improvisation. The fourth scale, termed a ‘Blues shadow scale’, is a major scale consisting of all the notes not in the ‘blues scale’ and starting a minor third lower, and thus generally dissonant with the backing music. This was added to encourage the players to be inventive and not to fixate on any one set of pitches.

These scales were then used as the basis for another collective improvisation but this time with the drummer playing in the background to keep up the rhythmic momentum. The conductor also began indicating to different sections of the band to take the lead at the improvisations at different moments:

Recording 4: https://soundcloud.com/oliverrudlandresearch/brassbandexcerpt-4

The band then added their own improvisations to the backing music, which they had already rehearsed. The solos from the recording of these improvisations were transcribed and then integrated into the score alongside the backing music. A selection of these solos is presented below in chronological order with the recording:

Example 3: Soprano Cornet in E-flat

Example 4: First Trombone in B-flat

Example 5: Euphonium in B-flat

Example 5: Euphonium in B-flat

Example 6: Second Trombone in B-flat

Example 7: Flugal Horn in B-flat

Example 7: Flugal Horn in B-flat

Recording 5: https://soundcloud.com/oliverrudlandresearch/brassbandexcerpt-5

The co-creative process did not stop with the improvisational workshop and continued in several ways. For example, not all the band members were as confident at improvising during the workshop such as the lead solo cornet player. Consequently, those players who felt less confident were invited to take the scale sheets away from the workshop and work on their improvisations individually. In response, the solo cornet player produced the following contribution:

Example 8: Solo Cornet in B-flat

In fact, what the solo cornet player decided was to anticipate a gesture in the backing music (written here in small noteheads) by playing it a tone higher in advance of each statement in the backing music, thus extending and enhancing the descending sequential passage. This sequence can be heard in the following recording from a public performance of the dance number that followed the workshop:

Recording 6: https://soundcloud.com/oliverrudlandresearch/brassbandexcerpt-6

This was a welcome addition as it provided some less busy material to contrast with the other improvisations. It also reflected something similar in the first four bars of the second trombone improvisation, which likewise closely followed the phrasing of the sequential passage in heterophony. Following the public performance, the score was updated to include some of these extra variations. Additionally, several players continued to elaborate on their solos in the performance:

Recording 7 (Video - https://vimeo.com/690611559):

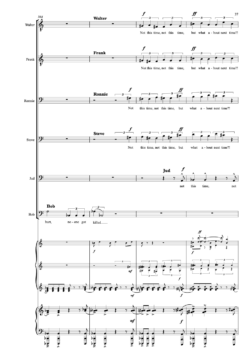

Then began the process of integrating the swing dance number into the community opera. The scene in the pub referred to above begins with this swing dance number. In a staged performance it would include both an onstage band and characters from the opera dancing to the music as a part of the scene. At a certain point, several characters (Shelia, Debbie, Mrs Casper and Reg) retire from the dance floor to sit down, and the focus of the drama shifts to their conversation. Reg offers to buy the other characters a drink and then visits the bar leaving the others to chat. On his return, whilst passing around the drinks, he makes the following statement:

Reg:

Here we are ladies,

bit of a ding-dong starting over there.

Been another fall down’t’ pit.

Best beware!

To set this text to music the soprano cornet improvisation was used as a basis around which the words were sculpted (see Example 9). However, a few minor adjustments to the rhythm were made such as the anticipation on the word ‘bit’ in the second and third bars (351–352). Some of the text is also extended melismatically to accommodate the whole of the improvisation, which has the dramatically appropriate effect of enhancing the urgency on the words ‘best beware’ by extending their length (bars 355–357).

The first system (presented in the key of D minor, that is, a tone higher than the original improvisation in C minor) follows the same backing music onto which the improvisations were made. In the second system the backing music introduces some fresh material modulating the improvisation up a major third while adding to the dramatic urgency of the text at this moment. This also distorted the improvisation so that the baritone voice (i.e., Reg) reaches a climatic F-sharp at the top of its tessitura on the word ‘beware’.

Example 9:

Similar alterations are present during the rest of the scene where other conversations take place, such as an agitated dispute between a group of miners who are discussing the accident down the coalmine to which Reg referred. Here the same soprano cornet improvisation is distorted further, culminating in a ‘questioning’ French Sixth sonority (F-sharp, A-flat, C, D) on the words ‘what then?’ as the improvisation is extended and tonally altered to match the harmony (top ossia stave, bars 373–376):

Example 10:

Conclusions

The combined process of a co-creative workshop and subsequent rehearsals and performance could be described as having replicated, under controlled conditions, the circumstances of the ‘band room’ and live improvised performance in which swing band dance music was historically brought into being (Tracy, 1997).

In doing so, this process assisted with generating an authentic sound to the swing dance number which mirrors both the historical period in which the opera is situated (i.e. during the 1950s) and the sociological circumstances of its setting, such as the adoption of brass bands in mining communities as instrumental alternatives to big bands because such instruments were available to them.

It might be imaginable to compose music in this style without such a co-creative process. However, this would be unlikely to produce the vitality and variety of responses of working with a real musical community, especially given that this was how this style evolved in the first place (Marsalis, 1995).

The risks of working with a brass band in this manner are that such ensembles are rarely accustomed to improvisation and prefer to read from notated parts. Therefore, a careful, flexible, and patient process as demonstrated, is required to tease out different responses from individual members, especially from those less confident or experienced at improvisation (Barrett, 2014). However, the rewards of this process can in some ways enhance the overall quality of the combined efforts by juxtaposing more flamboyant responses with simpler, more direct ones. This in turn can enhance the stylistic authenticity of the ensuing music, transforming performance limitations into aesthetic and dramatic advantages.

By integrating such responses into a scene for a community opera, the rewards go even further by providing musical materials through which the dramatic content of the story can be enhanced and conveyed with greater alacrity and sophistication. As well as transferring this stylistic authenticity into a dramatic realisation of the circumstances in which it was created, thus infusing the scene with a musical-dramatic realism.

This project also suggested areas for further practice research where other onstage or offstage band elements could be explored to reflect different settings and different sociological circumstances. Given the enormous array of historical contexts in which improvised music has played a social role, the possibilities would seem very considerable.

References

John Barber, 'Finding a Place in Society; Finding a Voice', in Beyond Britten: The Composer and the Community, ed. by Ghislaine Kenyon Peter Wiegold (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2015), 107–22

Margrett Barrett, eds. Collaborative Creative thought and Practice in Music (Surrey: Ashgate, 2014)

Kathryn Deane ‘In Search of Peterborough’, Sounding Board: The Journal of Community Music (Summer, 1995), 12–15

Jonathan Dove, Who needs community opera? https://www.traction-project.eu/who-needs-community-opera-part-one-lets-take-over-a-whole-town/ (2020) Retrieved 12.03.22

Jonathan Dove, ‘From the weaving-shed to the airport: experiences of writing opera for Glyndebourne and the Community’, Glyndebourne Season Programme, (1999), 121–125

David Hall, Working Lives (London: Corgi Books, 2012)

Trevor Herbert, The British Brass Band: A Musical and Social History (London: Oxford University Press, 2010)

Lee Higgins, Community Music: In Theory and in Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012)

Wynton Marsalis, Marsalis on Music (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1995)

R. Keith Sawyer, Group Creativity: Music, Theater, Collaboration (New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2003)

Omar Shahryar, The Composition of Opera for Young People (PhD, University of York, 2019)

Sheila Tracy, Talking Swing: The British Big Band (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 1997)

Julia Winterson, ‘So what’s new? A survey of the educational policies of orchestras and opera companies’, International Journal of Community Music, 3(3) (2010), 355–363

Endnotes

[1] Jonathan Dove, Who needs community opera? https://www.traction-project.eu/who-needs-community-opera-part-one-lets-take-over-a-whole-town/ (2020) Retrieved 12.03.22.

[2] Higgins does give a separate ethnographic account of the Peterborough Community Samba Band who participated in the performances of In Search of Angels. See: Lee Higgins, Community Music: In Theory and in Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 55–79.

[3] The evidence provided has been through the University of Leeds’s ethical review process (FAHC 20-024) and has the full permissions of the participants for inclusion in a published context. For these reasons the names of all the participants are identified anonymously and in reference to the instruments they play instead.

[4] For instance, the Bryntaf ‘Usherettes Jazz Band’ that was made up of miner’s wives which performed at dances and functions in workingmen’s clubs in the Aberfan and Troedyrhiw valleys. See: David Hall, Working Lives (London: Corgi Books, 2012), p. 74.

[5] It is common practice for group improvisations to be based on a simple song or ‘standard’. See: R. Keith Sawyer, Group Creativity: Music, Theater, Collaboration (New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2003), p. 31.